How to Choose the Right Essential Oil for Your Life’s Season

Introduction Our lives move in seasons — moments of growth, rest, change, and renewal. Just as nature shifts with the rhythm of spring, summer, autumn,

An individual responds to a social situation based on how they perceive it. Take the story of Romeo and Juliet, for instance—it would have had a very different ending if Romeo had believed Juliet was drugged instead of dead. This idea forms the foundation of much of modern social psychology. However, many contemporary social psychologists go further, asserting that the way we interpret social events—or the nature of social cognition—is not fundamentally different from how we interpret any other event, social or otherwise.

While many aspects of social psychology overlap with general cognitive psychology, social cognition has unique characteristics that make it inherently social. For instance, much of what we know, we learn from others. Human language serves as the primary vehicle of this cognitive interdependence, allowing us to share discoveries and pass knowledge across generations. In this way, we perceive the world not only through our own eyes but also through the perspectives of others, shaping our beliefs based on what others say or write.

A classic study conducted by Solomon Asch illustrates how even our understanding of physical reality is, at least in part, a matter of social consensus.

In this experiment, nine or ten participants were brought into a laboratory room and shown pairs of cards placed some distance away. On one card, a single black line of about 20 cm was drawn. On the other card, three lines of varying lengths—16 cm, 20 cm, and 18 cm—were displayed. Participants were tasked with a straightforward perceptual judgment: to identify which of the three lines matched the length of the single line on the first card.

However, there was a twist. Only one of the participants was a genuine subject; the others were confederates secretly working with the experimenter. The confederates had been instructed to respond aloud with their judgments, answering correctly at first, but eventually giving unanimous, intentionally incorrect answers in subsequent trials.

The key question was: how would the real subject respond?

Asch found that less than 25% of participants maintained complete independence in their judgments throughout the experiment. The majority conformed to the group at least occasionally, even when their own senses clearly contradicted the group’s unanimous (and false) responses.

When interviewed after the experiment, most conforming participants claimed the group had not truly influenced their personal judgments. But what interests us here is not so much what they did, but how they felt during the process.

The genuine participants, whether they conformed or not, generally reported feeling uneasy. This discomfort arose because Asch’s procedure violated a fundamental assumption of existence: the belief that, despite individual differences, all people share the same physical reality.

Why do humans assume the existence of a socially shared reality? Theories on this are speculative, but two possibilities stand out.

For example, something “real” tends to provide consistent sensory information. If I see a spoon but cannot touch it, I might still conceptualize it as a spoon based on visual consistency. Another criterion is what philosopher John Stuart Mill called the “permanent possibility of sensation”—the idea that something real exists consistently over time. For instance, we can look away from a building, but when we turn back, the building is still there.

In adults, this understanding of physical reality as independent of momentary perspective is deeply ingrained and rarely questioned. When challenged, it can provoke significant discomfort.

The belief that others see, hear, and feel the world in ways similar to us becomes a cognitive axiom—a fundamental assumption underpinning our everyday experiences. This shared understanding of reality helps us navigate the world and interact with others, but as Asch’s study demonstrates, when this assumption is threatened, it reveals how deeply intertwined our cognition is with social agreement.

Introduction Our lives move in seasons — moments of growth, rest, change, and renewal. Just as nature shifts with the rhythm of spring, summer, autumn,

Imagine walking into a space that instantly soothes your spirit, calms your mind, and feels like a gentle embrace from nature itself. That’s the power

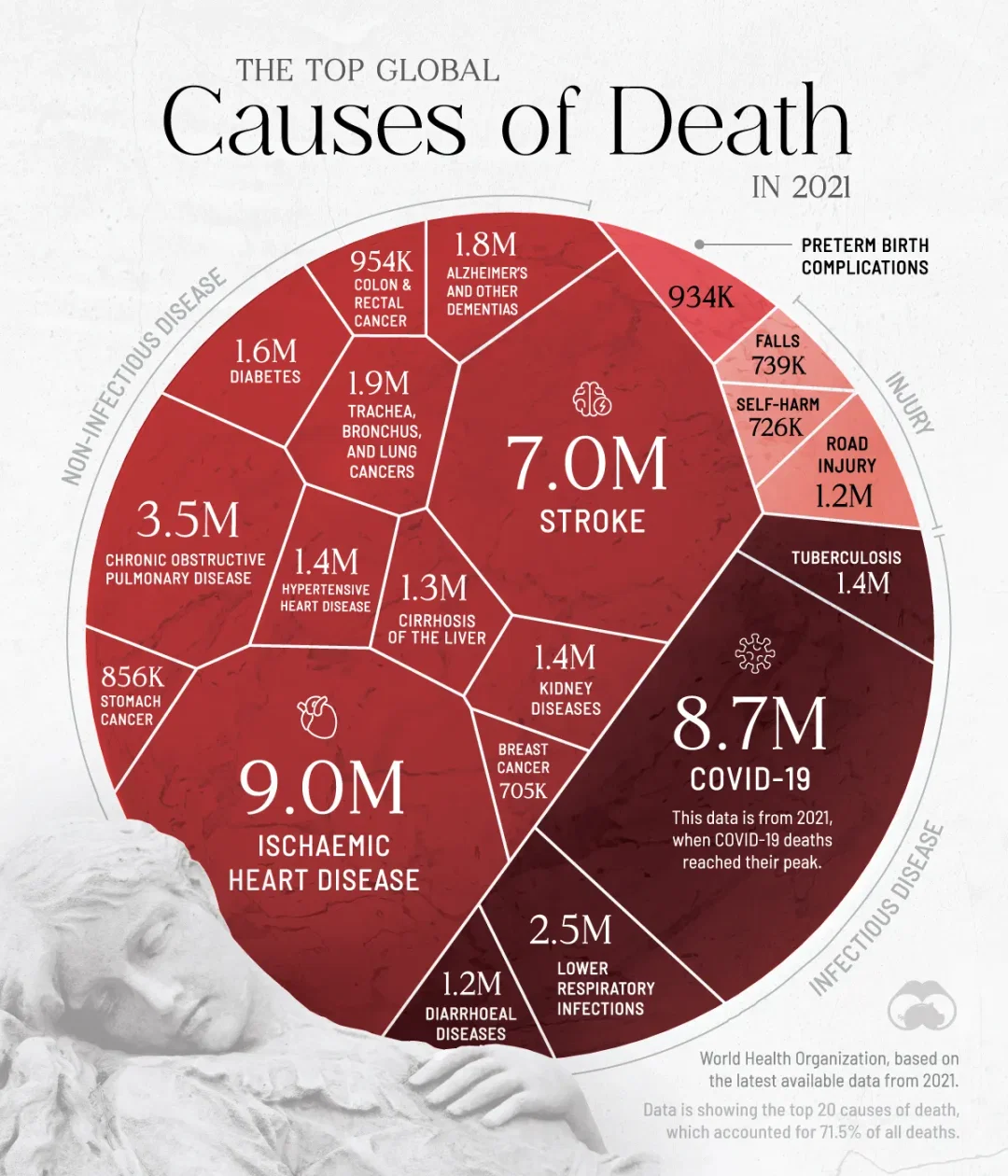

Every year, millions of people around the world lose their lives to just a handful of diseases. In fact, about 70% of all deaths are

What is the 08/08 Portal? Every year on August 8th, the powerful Lion’s Gate Portal opens — a cosmic alignment between Earth, the Sun, and

Have you ever felt disconnected from your higher self, experienced mental congestion, or found it hard to trust in your path? These may be signs

Do you sometimes feel disconnected from your intuition or experience mental fog? These may be signals that your Third Eye Chakra—also known as Ajna—is out